Putin gives a speech and the rouble falls. Europe’s central bank boss gives a speech and the stock markets fall. Opec meets in Vienna and the oil price plummets. Japan’s prime minister calls a snap election and the yen’s slide against the dollar accelerates. All these things in the last six weeks of an already fractious year.

There are suddenly multiple conflicts being played out in the global markets, conflicts the global game’s usual rules are not built to handle.

The first concerns a clear game of beggar thy neighbour between China and Japan. Since 2012 Japan has printed money hand over fist, with the aim of kickstarting economic growth. With growth stalling for a third time in the final quarter of 2014 its premier Shinzo Abe printed more. China perceives this as unfair competition, and with its own growth slowing, it responded in late November with a surprise interest-rate cut.

Many see this as the outbreak of a classic currency war, along 1930s lines, where rival economic giants engage in a pointless game of devaluing their own currency – boosting exports but hitting the spending power of their people – to their mutual detriment. By hitting each other’s capacity to export, they edge the region towards deglobalisation.

The second new dynamic is the game of chicken being played over the oil price between America, Russia and Opec. Oil demand is falling because growth in the emerging markets – China, Brasil and the like – is slowing down. Yet supply has risen – by 11m barrels to 92m barrels per day since the global financial crisis began. America has become the world’s biggest oil producer thanks to the rapid rollout of shale and deep sea oilfields. Since June 2014 the price of a barrel of Brent crude has fallen from $115 to $68 – and after Opec met in late November and rejected calls to cut production some analysts predicted the price could collapse to $40. Saudi Arabia and the other gulf monarchies were the key players in the decision to keep production high and prices falling – and few doubt there is politics behind the move. It hurts Russia, Venezuela and Iran. For Saudi Arabia there are scores to settle with both Russia and Iran over their role in crushing the Syrian revolution, and with Venezuela for being Russia’s perpetual Bolivarian cheerleader. As a result, Vladimir Putin has had to admit to his people that a combination of western sanctions and Saudi oil strategy will push Russia into recession next year.

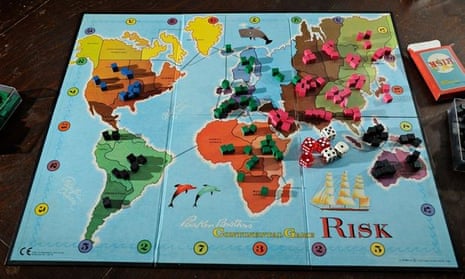

At times like this economists resort to game theory, warning sparring countries that, in a game where everybody is trying to shrink something – whether it be prices or currencies – everybody loses out. So let’s game it out – not in the austere language of theory but of the empire-building “god games” popular on games consoles.

Empire A is a rich, stagnant ageing country, paying itself high social benefits but running debts at 250% of its annual output. That is Japan.

Empire B is a poor-ish and also ageing country, ruled by a dictatorship, which has achieved high rates of growth and modernisation but has now slowed down. That is China.

Empire C is run by a lunatic. It has invaded a neighbouring country twice in 12 months, has its warplanes buzzing a historic foe – and has a bloated upper-middle class in a state of near panic as its currency tanks. It is more or less totally dependent on the price of oil and other global commodities. I don’t need to name this country, but if you are unlucky enough to be anywhere near it in the computer game, it is making you very worried.

Now let’s look at Empire D. If you’d been playing this side in a game set 800 years ago, when it was called the Holy Roman Empire, you’d have been worried about its eternal fractiousness; its ethnic and religious strife – and the fragility of its governance systems. And if you’ve any sense, you still are: half of its economies are stagnant. This is Europe, and it is the only one of our global players that is not supporting itself by printing money.

Finally, Empire E. After marauding across the globe for a century in search of oil it has suddenly become self-sufficient. It has a paralysed governance system and a fractious civil society, but nothing the flickering spectacles on its plasma screens cannot pacify, together with a few tasers. That is America.

As long as the game is collaborative, four out of five players can pursue their aims to mutual benefit. Japan can enjoy happy stagnation, China brutalist growth; the EU can stagger from crisis to crisis; America can shoot its own citizens and drone-strike its enemies. Only Russia is in trouble.

The real problem comes if the game atmosphere turns overtly competitive. That is, if the players perceive themselves to be fighting over shrinking resources, shrinking growth – and to be in a game where pure selfishness is the optimum strategy. Think of this this way and the real story of 2014 becomes clear.

In 2014 Russia’s perception of its “game” with both Europe and America has became purely combative. Reluctantly, these other two players recalibrated their stance, while trying to maintain the global rules as collaborative. But in the last quarter of the year, the game has also changed between China and Japan.

Europe wants competition with nobody, and its central authorities are paralysed where it matters most: monetary policy. It is an entity modelled on the old, collaborative game rules and unable to conceive of operating without them.

If this was a game played in annual turns, the umpire would probably call some kind of time out at Christmas. And in that pause it would be sensible to say: “Ladies and gentlemen, there are clear signs that the rules of this game are about to invert. Are you completely sure you want to go on to the 2015 turn with the same strategy?”

Paul Mason is economics editor at Channel 4 News. Follow him @paulmasonnews