By Professor Stephen D. Solomon, Editor, First Amendment Watch

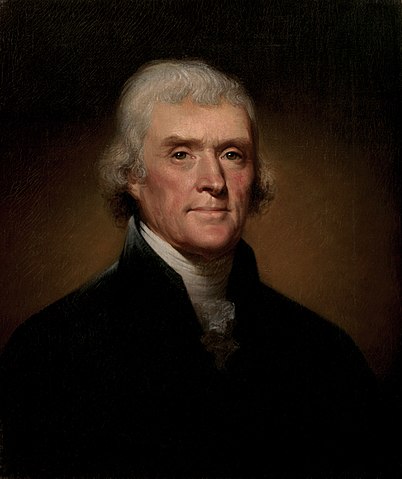

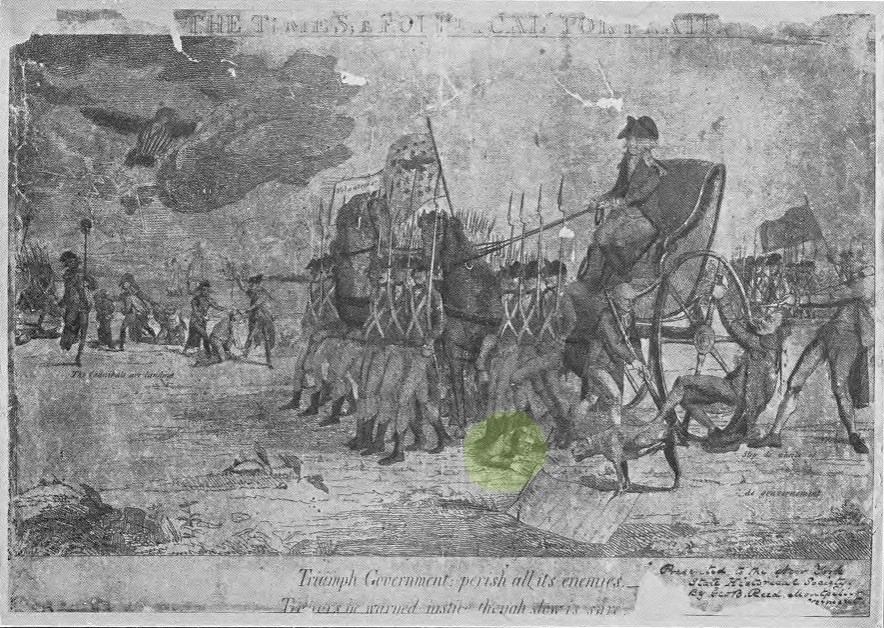

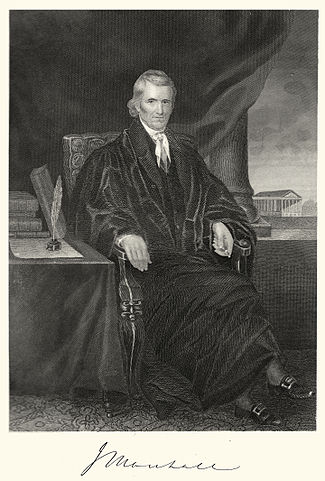

On March 4, 1801, Thomas Jefferson delivered his First Inaugural Address in the Senate Chamber before taking the oath of office administered by Chief Justice John Marshall. He became the nation’s third President amidst the fires still burning from the odious Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798. Under the Sedition Act, the Federalist Administration of John Adams had jailed more than a dozen Democratic-Republican political opponents for their speech or writing. Jefferson, vice president under Adams, and James Madison had opposed the Acts in their Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions, written in secret. In large part as a result of this political repression, Jefferson prevailed in the election of 1800 and the Federalist Party began its spiral into oblivion.

Jefferson delivered a conciliatory address, and in the excerpt below he argues that difference of opinion “is not a difference of principle.” All Americans were united—“we are all republicans: we are all federalists.” And freedom of expression should protect all, even those who preferred dissolution of the country—“let them stand undisturbed as monuments of the safety with which error of opinion may be tolerated, where reason is left free to combat it.”

Thomas Jefferson’s First Inaugural Address

“All too will bear in mind this sacred principle, that though the will of the majority is in all cases to prevail, that will, to be rightful, must be reasonable; that the minority possess their equal rights, which equal laws must protect, and to violate would be oppression. Let us then, fellow citizens, unite with one heart and one mind, let us restore to social intercourse that harmony and affection without which liberty, and even life itself, are but dreary things. And let us reflect that having banished from our land that religious intolerance under which mankind so long bled and suffered, we have yet gained little if we countenance a political intolerance, as despotic, as wicked, and capable of as bitter and bloody persecutions. . . [E]very difference of opinion is not a difference of principle. We have called by different names brethren of the same principle. We are all republicans: we are all federalists. If there be any among us who would wish to dissolve this Union, or to change its republican form, let them stand undisturbed as monuments of the safety with which error of opinion may be tolerated, where reason is left free to combat it.”

Members of the House and Senate rose to their feet in the Senate Chamber, a large semicircular room with an arched roof and spacious gallery. Senators sat on one side of the chamber, and the other was given over by the members of the House to the women who were in attendance. Aaron Burr rose to relinquish the chair of the presiding officer of the Senate, which he had temporarily occupied, to Jefferson. After a short pause, Jefferson stood to deliver his speech in a room that was, Margaret Bayard Smith claimed, “so crowded that I believe not another creature could enter,” and that according to newspaper reports held the “largest concourse of citizens ever assembled here.” The Aurora reported an audience of 1,140 (of whom about 154 were women) in addition to members of Congress. After delivering his address in “so low a tone that few heard it,” Jefferson seated himself for a short time and then proceeded to the clerk’s desk to take the oath of office, which Chief Justice John Marshall administered.

Members of the House and Senate rose to their feet in the Senate Chamber, a large semicircular room with an arched roof and spacious gallery. Senators sat on one side of the chamber, and the other was given over by the members of the House to the women who were in attendance. Aaron Burr rose to relinquish the chair of the presiding officer of the Senate, which he had temporarily occupied, to Jefferson. After a short pause, Jefferson stood to deliver his speech in a room that was, Margaret Bayard Smith claimed, “so crowded that I believe not another creature could enter,” and that according to newspaper reports held the “largest concourse of citizens ever assembled here.” The Aurora reported an audience of 1,140 (of whom about 154 were women) in addition to members of Congress. After delivering his address in “so low a tone that few heard it,” Jefferson seated himself for a short time and then proceeded to the clerk’s desk to take the oath of office, which Chief Justice John Marshall administered.

Source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Volume 33, 17 February to 30 April 1801 (Princeton University Press, 2006), 148-52

Tags