The clothing firms designing clothes that last forever

- Published

- comments

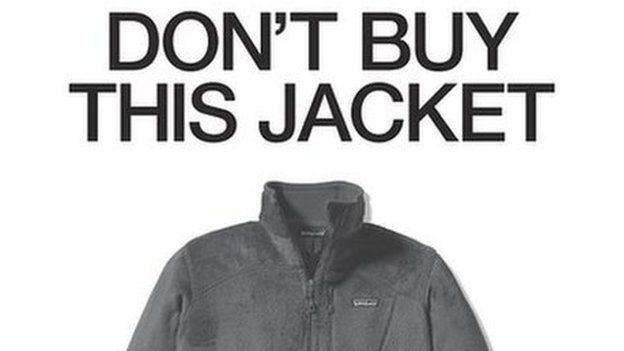

"Don't buy this jacket" is an unusual advert for the company that makes it to run.

Yet in late November 2011, outdoor clothing business Patagonia did exactly that, taking out a full page in the New York Times, explaining the environmental costs of manufacturing the item, and asking people to think twice before they bought one.

It has done a similar campaign - asking people to buy only what they need - around the same time each year since. And almost in direct correlation its sales have kept rising, with this year expected to be the most profitable in the Californian firm's 45-year history, with predicted sales of $750m (£495m).

Telling people to buy less seems to have spurred them to do the exactly the opposite.

Patagonia's chief executive Rose Marcario rejects this, arguing that its campaigns have made like-minded people want to shop there, and alongside a wider distribution network, has helped it to gain market share.

For her, the company's growth is proof that its view of capitalism - taking its impact on the planet as seriously as the financial metrics - can work.

Patagonia guarantees its clothes for life, and offers repairs "at a reasonable charge" for normal wear and tear - it estimates it'll do 40,000 individual repairs this year.

It also invites people to share stories of their favourite old items on its blog, and helps customers swap or recycle clothing. And since 1985 it has given 1% of its revenues each year to environmental groups, amounting to around $70m so far.

A small revolution

Businesses can be a "positive agent for change," insists Ms Marcario.

"For us it's not a contradiction. We want people to buy better quality, durable goods, and at the end of their lives recycle them," she says.

The US firm is one of a small number of clothing companies actively countering the proliferation of cheap wears, where new collections delivered weekly, or in some cases daily, has helped fuel a seemingly insatiable desire to buy more stuff.

The fact that many of the items are so cheap - a £10 top or £20 dress - makes it easy to buy stuff, increasingly items of clothing we don't actually need, and then just as easily discard after they have been worn a couple of times, or even never.

This year, in the UK and the US, consumers are expected to spend more than ever before on clothing and accessories, £53.5bn and $274.8bn respectively, according to market research firm Mintel.

Such overconsumption is taking its toll on the environment, with UK government agency Wrap calculating that some £140m worth (350,000 tonnes) of used clothing goes to landfill in the country every year.

'Absence of need'

But are companies - which clearly benefit the more we buy - really the ones to try and push the change?

Kate Fletcher, professor of sustainability, design, fashion at the London College of Fashion, is sceptical.

She notes it's "canny" for businesses to try to give their products more meaning.

"People are looking for values in products," she says. "It's a response to an absence of need. Companies have seen a gap and are setting out a different sort of purpose which fills those needs."

As part of her research Ms Fletcher has spent time studying the clothing people hang on to, and found they're rarely garments designed to be durable, but ones they've become attached to.

And she also notes that buying one meaningful durable item doesn't stop people buying more.

"People have an infinite capacity for every more meaningful garments," she says.

Nonetheless, she believes making people more aware of the effort and resources that go into making clothing would help to provide greater respect for them, and make people less inclined to discard them.

It's something that Carin Mansfield, founder of clothing brand Universal Utility, is trying to do.

Walking into her minimalist, small four-storey shop, In-ku, on a central London side street, with white washed walls and just a few garments hanging on hooks on each floor, is a complete contrast to the busy, crowded shops just a few steps away on Tottenham Court Road.

The clothes she makes are inspired by old workwear. Pre-washed so they won't shrink further and slightly crumpled, the loose fitting garments are sewn precisely, with all raw edges hidden.

Her three London-based machinists make each garment individually, rather than parts of the whole such as in a factory, and are paid per item of clothing, rather than by the hour.

It means there's no economy of scale, and Ms Mansfield says that to create garments in this work intensive way "you've got to be a slight maniac".

She spent two decades working like this as a wholesaler, including a 10-year collaboration with Comme des Garcons, but rejected an offer from the Japanese fashion label to make her clothes under licence, after seeing the samples and realising it just wasn't possible to scale up her work without significantly compromising the quality.

Instead she set up the shop, where each item costs an average of £500. To make sufficient profit, she should charge between £800 and £900, but she says it's "hard enough" to sell them at their current price.

Explaining why the clothes cost so much is difficult she says, adding that sometimes you sound too much like you're trying to sell them, and the vast majority of customers aren't interested.

After two years in business, she takes a small salary, but is not in profit. But she says she's okay with the fact she hasn't made a fortune.

"Making something of quality that is appreciated is worth lots more in the end," she says.

Tom Cridland, founder of his eponymous menswear brand, makes trousers, t-shirts and sweatshirts that are guaranteed for 30 years. He is adamant that it is possible to make durable, higher quality items profitably.

On both his sweatshirts and trousers - which cost £55 and £89 respectively - he makes a decent profit, and sales totalled £250,000 last year. He says he's transparent about his costs because he wants to encourage other fashion retailers to do the same.

The brand is just two-years-old, meaning that it's too early to tell if the items really will last for three decades.

The idea, he says, was initially a way for him to try and get exposure for his company in a crowded marketplace, and has resulted in what he says is a "more gimmicky" brand than he originally envisioned.

But he says it's also persuaded him of the merits of sustainable fashion for customers and the planet.

"It's fair to expect obsolescence in terms of trendy items, but not when you're selling a white t-shirt."